1978

Jean Narboni and Serge Daney

Serge Daney and Serge Toubiana

interviewed by Fabrice Ziolkowski

on LES CAHIERS DU CINÉMA

July 1978

FZ: I’d like us to talk about the period of the Cahiers from the time when there was still an interest in the American cinema (1968-70) up to today. Specially what you’ve been doing in the last three years and what you’re moving towards.

Toubiana: It’s interesting to start that way. Why did texts stop being translated in the U.S. and elsewhere? Effectively this period which begins in mid-1972 (#242) is a typically French period when the Cahiers really enter French ideology of the moment. It was a period of crystallization on the political discourse, we tightened ourselves around the master’s discourse of the Marxist-Leninist movement with our thoughts turned toward the Chinese Cultural Revolution. This period is not really translatable and would most likely be of no interest in translation. We entered a period, if you like, of the French context, context of the Leftist French Intellectual.

Daney: We can also make a point here. The English translation of Cahiers by Sarris was happening at a time when American Cinema was still very important for the French critic, from this period (1966) up to now there hasn’t been anything translatable into an Anglo-Saxon context, political or intellectual, from Cahiers. We come to the specificity of the French situation, be it on a theoretical level and on the political level. The theoretical texts can always be re-appropriated after ten years, which is what seems to be happening in the U.S. and in England. It’s evident that the purely political period of Cahiers is untranslatable, that if it was, it would give birth to monsters given the differences in American and French intellectual lives. Of course, I saw people in New York like Bill Starr who are “militants” and their discourse is poor including in relation to what was already poor here then. It’s totally without life, while we can say that this hard and rigid discourse, at the time, was also accompanied by a certain passion, which is important. When people today come back on those texts, the passion has left, and all that is left is the letter of the texts which is frightening, like any letter.

FZ: Fred Guynn’s article in JumpCut* is an example of this. It only supports its arguments through the texts.

Toubiana: That’s something we also did though. In the little world of Marxism-Leninism, everything is judged by the text. This comes from a Bolshevik tradition. The dogmatics have always claimed that truth and falsehood were written. We did the same thing: "X thinks this, because he wrote this.” There’s nothing surprising about somebody else doing it to us.

Daney: Something irritated Narboni and I a little bit in Edinburgh last year. The problems of art, culture and theory that we had faced in this time of politicization, were coming to a country like England quite a bit late, and were being dealt with by people who were calling themselves Althusserians, but who were forgetting to do what Althusserians everywhere do, that is history. They had no curiosity for this specificity, of the history of the relationship between intellectuals and Leftist politics in France. On this, there’s the risk of doing an ahistorical work, university-like and academic. There’s a debate about the intellectual and the masses that’s been going on for 100 years and we’re only one part of that debate. It’s evolved differently in the States, that’s a text for YOU to do.

FZ: How long did this period last?

Toubiana: Properly speaking, the Marxist-Leninist period lasted from #242-43 in which we got rid of the photos. Which instead of fetishizing the photos, fetishized the texts. It went to issue #250 in which there is the editorial re-defining the review’s stand, leaving the Marxist-Leninist ghetto.

FZ: Why have you entered and then left the Marxist-Leninist movement?

Daney: All the cultural people were behind in politics. The height of Marxism was probably 1970, Cahiers plugged into it when it was already in decline but we didn’t know it yet. Cahiers and Cinethique were the only ones to have taken seriously, albeit later, what had moved politically during those years. It was something going around Paris. It had affected reviews like Tel Quel and at the university there were some very politicized students, this all precipitated our move.

Toubiana: A very concrete example. In February 1972 there was the demonstration at the burial of Pierre Auvernay.** It was the sum of Leftist activity and the beginning of the end, the largest Leftist demonstration in France (200,000 people). The Cahiers people went to it and from then on, the review was a place where Marxism-Leninism was discussed, while the Auvernay demonstration was the end of the Maoist movement. The entertainment people also showed up. It was also an opportunity to see the PC under its ugliest mask. It put the murderer and the victim on the same level. There was a sensibility with the “petits bourgeois” who wanted to politicize themselves while the people interested in Marxism-Leninism were in a period of decline.

Daney: After that, there was a traditional period when Cahiers was thinking of its political activity in regards to a Party (to be built) although it was evident that the small groups would never build this party. There was a polemical and hysterical position in regards to the PCF which was ten years too late on everything concerning Cultural Front activity (theory, cinema), something it has somewhat made up today. There was a second period in which certain words can help us. The word “power” came at one moment, synchronically with Foucault... We can say that our cinephilia helped us to go forward. For a cinephile, the power of the cineaste, even if it’s really imaginary, is ours of proportion socially and real in regards to what he manipulates as material. Therefore, we see a moral preoccupation which comes back to Bazin, which is to evaluate films not really on their aesthetic quality but in ethical terms. It’s a period when we speak of “direct.” Then there’s a third period when, from the idea of power, we moved to the realization of the power of media. Power today is the new management of media which is a problem on which the Leftists have been nil, pre-historic, with the exception of someone like Baudrillard. But let’s say that, in general, Marxist reflection on media is nil. This is a little bit the Mattelart period.*** From then on we saw how we could re-interest ourselves in cinema, in films that were coming out, to become once more a film review while being a little bit ahead which consists in recognizing that film is one piece in the more general game of the media and that we can’t disassociate them. To approach these media, everything we learned before 1968, in psychoanalysis for example, is helpful.

Toubiana: I think you’re going a little too fast because there have been other words too. My thesis is that may exist from dogmatism is done on the empirical and populist mode. When you come out from a strong discourse, a little bit paranoid, you only do so through a return on your base where you try to see what is being done on a popular level in the area you’re working in. The fetish words at the time are “popular culture” and “ideological struggle.” In the table of contents of #250 you see the Editorial, “Popular Culture” and “Militant Work,”“Collective Film” and “Critical Function” where Cahiers fights an ideological struggle against films with reactionary political content: Lacombe Lucien and Night Porter. We only leave the period where we lost the cinematic referent by returning to it in a more populist fashion. We invented some words like “popular culture” which doesn’t exist, isn’t definable. From there you come to today when we’ve rectified a lot of things. A deviation always supposes a counter-deviation.

Toubiana: It’s a violent return which doesn’t go far enough or goes too far. It was also done at the price of sacking one person in particular. It wasn’t done without a crisis.

Daney: This pendulum movement also follows a logic. The subjective drama of the intellectual is that he is in the service of ... he thinks himself as responsible, either in the service of a party or in the service of the masses. Cahiers lived both phases rather quickly before finding an anchoring place where are found certain cineastes who work this situation from a filmmaker’s point of view. This lets us re-question the cinema. But more and more from the standpoint of individuality. It’s a kind of very selective “politique des auteurs” which capsulates a period with Straub and Godard. Today, since we’ve got a little critical distance from them, we see they asked themselves these questions from an individual, not individualistic point of view. Pudovkin at the end of his life, Godard when he deals with television and Straub behave like little states, little powers, and if they think out the great debates in their times, they do so from a position which is theirs and only theirs. It's always the same debate but more collective in large units and crystalized in one film practice. Since it was already the cinema which, in our capacity of simple cinephiles, we lived before '68, we came back on our feet: Godard, Straub, Robert Kramer, Moullet, etc. Today we can say that a guy like Syberberg, who’s a more ambiguous filmmaker, also functions in a totally paranoid way, which isn’t negligible, like a small power in relationship to producers, the Party and cinema.

Toubiana: We also forget the word we used at the time: Cultural Front, i.e., an alliance with other artistic practices. We saw at the end of a year that a film critic couldn’t ally himself with a painter.

Daney: It’s from this position of greater power, social, aesthetic and artistic that an intellectual can speak. The last time we saw Bertolucci after The Conformist, we were very rigid and he was already very opportunistic, he said that he had done The Conformist as well as militant films for the PCI on textile workers. It was very evident that he was putting 0.5% of his power into the militant films. It was Godard who put everything into it, that is the level of a great cineaste and enough power to do experiments, he's still going today.

FZ: People who've always taken risks?

Toubiana: I don't think Godard sees it as a risk. He lives it as a normal evolution.

Daney: He sees it as a rivalry between himself and the rest of them. When he said "France mise en scene by Pompidou and Marcellin," it's evident he sees these political men as other filmmmakers. Like Syberberg with Hitler. It's a mad rivalry. It's a settling of accounts with the same weapons: money, and power.

From these we can see other ties from before the political period. A dogmatic cinephilia which extends its hand to dogmatic politics. Cahiers with Godard, Rivette, Bazin, had an arbitrary, cut and dry vision, -- ethical, unjust, polemical. There was always the question of liking one film over another, of liking one film against another. That hasn’t changed.

Toubiana: The worst period of the Cahiers is that after this dogmatism when we thought militant cinema was going to work. In this cinema there is no question of judging the quality of a film, we can only say, “It’s good for the public to which it’s addressed.” Never cutting to say whether it’s a good film or not, one where there is work or not. That was a pretty short period from which we came out with an issue on Straub. Milestones (Robert Kramer) was for us the positive example of militant cinema. We mystified it into the message from America.

FZ: It’s interesting there to see the gap between France and te U.S., Milestones being a film little seen in the U.S.

Toubiana: That’s another thing that’s always gone on.

Daney: It’s something to do with our relationship to American cinema, militant or not. We like Milestones, in regards to the kind of cinema it is. “Progressive” ideas in an Arthur Penn film, for example, were of no interest to us. There’s a great deaf dialogue between the U.S. and France concerning what’s good in American films. Cahiers has always defended the products which Hollywood wasn’t too proud of. I think there’s a re-appropriation of this today since film is being taught increasingly in U.S. universities. It still goes on like Hitchcock and Hawks today with people like Monte Hellman or Cassavetes. Let’s say American film after Arthur Penn and Altman made a cinema which has reacted against the spirit of American cinema (Hollywood films, a reactionary spirit), but which hasn’t touched the letter very much. They film a little less precisely than before. If we’re interested in (Robert) Kramer, it's because he can take up, to the letter, the same shots as Ford, for example. Cassavetes because he's a part of Hollywood fighting Hollywood. The critical viewpoint Americans can have today in regard to their own mythology is not interesting to us, because we did it before them. It's more interesting to see what's done with the letter, on ecriture. It's evident that The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is a thousand times stronger than Penn because of what stays on the level of the letter.

FZ: What kind of tools have you been using to analyze film? I see the influences of psychoanalysis in writing like Bonitzer’s or Pascal Kane’s. There’s been an interest in photography, in video, etc.

Daney: The most Lacanian texts of Bonitzer’s are before the Maoist period. We’ve always had a reaction against the idea of “purity” of cinema. Bazin was interested in TV at a time when it wasn’t seen very much. What we’ve always seen as the best part of French cinema is the most literary and theatrical part, it’s a literary cinema. From Abel Gance to Duras, that’s been the case. This refusal of a “cage” marked Cinema is still going on. We’ve always thought that cinema is defined by what it wasn’t but positively not negatively. It’s always by the meeting of film with something else, like politics, that there’s movement. There’s also the “crisis” of cinema. It’s evident that its place in the other media is going to be redefined. It’s a crisis of the “machine” of French production, not of talent.

FZ: You haven’t gone through the Maoist period to return to the same kind of cinephilia as before?

Daney: No, but everything I said about the letter, about literality, stays the same. Maybe we can better theorize it today.

Toubiana: The old cinephilia supposes the concept of the series. If Ford did one or ten good films, it’s because he did so many films to begin with. All the great filmmakers worked in conditions that allowed them to build an “oeuvre,” a series of films, a kind of factory system (studio) with rebels and other workers who accepted the situation with the bosses. This condition isn’t around anymore. Today’s cinephilia supposes an average (medium) production (France is certainly the place where the average production is worst). Individual works stand out very well, on the other hand. These auteurs we defend are not in a position to work in series, although they're nostalgic about it. The only one who still uses these methods is Godard who says, "You must give me 10 hours of TV time to make 10 films." There's a sort of madness there, to consciously impose on yourself a studio production pace, as if a producer was pushing him. He's got his own studio, factory, he hires technicians, etc. Straub, on the other hand, can't work that way, because he's attracted to literature, the concept of the work. He has to redefine his position each time.

FZ: Straub brings in the question of avant-garde. Can we keep the distinction of Peter Wollen who writes of two avant-gardes and what is your interest for these filmmakers?

Daney: It’s a question of words. If we take the word “avant-garde’ it means those who are ahead of the others, implying that the others will one day go through there.

FZ: Is it a problem of taxonomy then?

Daney: Either it’s a military (spatial) definition or it goes back to something which has existed since the beginning of cinema. When today we see the films of L’Herbier, Cocteau, Man Ray, they’re still avant-garde, they’re still far from the rest. They’re people who defined themselves generally in relation to painting, outside of the industrial machine of film. “Avant-garde” in the Cahiers sense would be people who have cut a path for others: Cocteau, Bresson, Antonioni. People who did work in an industrial system. The role of a film review is to understand at any one time what is done that is new. In our view, to see this in close contact with the “enemy,” where things are the most dangerous, the most risky. Bresson doing Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne in the production system is more important to us than some guy experimenting alone in a corner, although it’s not “one or the other.”

Godard has always made films that questioned cinema. When I saw Les Carabiniers, it seemed obvious to me that you could never make a war film like before anymore, like Walsh's Objective Burma!. It's not the feeling you got when you saw a film by Marcel Hanoun or Malcolm LeGrice. There's another tradition, one which keeps the concept of craftsmanship from the industrial system but which dismisses the rest. The avant-garde is also a phenomenon which is tied to the art market not like it is tied to the rest of cinema. We're interested in the meeting of the two.

Toubiana: The filmmakers that interest us are those who submit themselves to the same verdict as commercial cinema. Straub said Othon was made for workers and peasants, for example.

Daney: If he didn’t say that, he wouldn’t have the strength to do it.

FZ: Is therefore the place where the writing is read more important than the writing itself?

Daney: There’ll certainly come a day when Straub won’t be able to make films outside of Beaubourg.**** It’s a tendency that goes back to the origin, in America, of the avant-garde to painting. The people who used to do Cahiers, and still do them today, learned to love cinema under very precise conditions and it’s not evident that we will learn to look at films like at paintings.

FZ: Do you think Cahiers will begin to explore this different kind of cinema?

Daney: Something that’s always irritated me about the avant-garde is the discourse it holds about itself. Peter Wollen says that there are two avant-gardes, one from the “realism” in cinema and the other which also holds a discourse on “purity” as the first one does (with Bazin, Eisenstein, etc.). There’s always a bad Other, in the case of Eisenstein and Bazin it’s naturalism, and in the case of the other avant-garde it’s narration. The thing I heard most in the U.S. was “non-narrative” cinema which to me doesn’t mean anything. It’s understandable, because if they want to distance themselves from narrative it's simply because they've been the best storytellers in the world. Nobody will ever do better than Hitchcock and Ford to tell a story.

**Pierre Auvernay, worker killed by a factory guard. The guard was recently shot and Auvernay revenged.

***Mattelart is also known for his HOW TO READ DONALD DUCK.

****Beaubourg: Le Centre National d'Art et de Culture George Pompidou

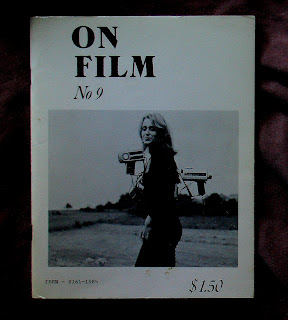

Originally published in ON FILM, No. 9, Winter 1978-79 (ISSN - 0161-1585)