JEAN GRÉMILLON

by Bernard Eisenschitz

He was one of the latecomers to the French avant-garde of the 20s. The traditional, almost obligatory manner of his arrival—a young man presents himself at the Vieux-Colombier with his reels of film under his arm; Jean Tedesco programs the film and the controversy gets under way—should not blind one to the usual coupling in his three silent films (Un Tour au Large, 1926; Maldone, 1927; Gardiens de Phare, 1928-29) of sophisticated structures culled from Impressionism with the regional background and "documentary" reconstructions which were often to be held to epitomize Grémillon. He thus becomes the poet of Normandy, Brittany, the men of the sea and the land. Of greater importance during this period of technical discovery, it seems to me, is the assimilation of the concept of cinema as an art of synthesis, employing the widest possible variety of techniques. For Un Tour au Large, Grémillon himself composed a musical score, using a short-lived synchronization process. The optical track, in other words, was only one of a series of techniques, and it is no accident that in 1946, in an article analyzing "the soundtrack" (La Revue du Cinéma No. 1), Pierre Schaeffer drew his examples from Grémillon when he wrote: "One can therefore say that the text is much less important than the intonation given to phrases, the texture of the voices, even the degree of intelligibility. . . The text must impose itself on the microphone, just as the image imposes itself on the camera."

Concerned above all with creating a popular cinema, Grémillon was able to attempt this only on the basis of a highly intellectualized mastery of the instruments of cinema. Hence the unusual, the sense of strangeness arising from the paradoxical confrontation of Grand Guignol (Gardiens de Phare) or melodrama (La petite Lise, 1930) with the subtle interplay that produces, in the latter film, a fusion of sound and image scarcely inferior to Renoir's La Nuit du Carrefour.

During the first ten years of the sound cinema, while young filmmakers were being brought to heel and integrated into the anarchic French and European production systems, Grémillon made a series of films without individuality. Yet Gueule d'Amour (1937) and Remorques (U.K.: Stormy Waters, 1939-41) each introduces a contradiction: in the first, two Hollywood types (the femme fatale, the Legionary) are subverted; in the second, two myths of French populism (Jean Gabin and Michèle Morgan) are deflected into becoming social representatives (and not types). Grémillon belongs to a politically progressive tendency—a tendency which producers and critics have all too often contrived to stifle. Exemplary in its difficulties, his career remains consonant with that belief in the artist's responsibility referred to by Louis Daquin: "Aesthetic and technical con-siderations were soon abandoned in favour of a problem which was still rather confused in my mind: a man and his craft, the creator and his art, the artist and his public, with all the responsibilities that ensue."

More generally known is the battle Grémillon waged as a film-maker under the Occupation, both through his portrait of a degenerate society in Lumière d'Eté (1943) and through the lofty sentiments extolled in Le Ciel est a Vous (U.S.: The Woman Who Dared, 1943), which was taken by French audiences as a call to arms. Paradoxically, following the hopes of 1945 and 1946, the post-war period was one of ominous regression. With Bresson and Tati consigned to a marginal place in the cinema and remaining silent for years, Grémillon expended himself in projects which would have revived the mass spectacles (e.g., La Marseiliaise) of Popular Front days. After the shelving of Printemps de la Liberté (about the 1848 Revolution) and Massacre des Innocents (about the Spanish Civil War), he was effectively eliminated from the French cinema and reduced to making short films, a format to which he returned for the last years of his life and perhaps—aesthetically speaking, as well as in terms of natural harmony and the unity of his work—for some of his finest films. Needless to say, the borderline between documentarist and fiction film-maker is not very distinct; the two approaches go hand-in-hand, and the concern for composition in Le 6 Juin à l'Aube (1944-45) or André Masson et les Quatre Elements (1959) is as acute as in any of his fiction films. Describing Le 6 Juin à l'Aube, Grémillon said: "Don't forget what materials I was working with: mines, stones, trees, fragments of statues. It was by arranging these images in time, according to a musical scheme, that I was able to give these inanimate and impassive objects a certain emotive quality."

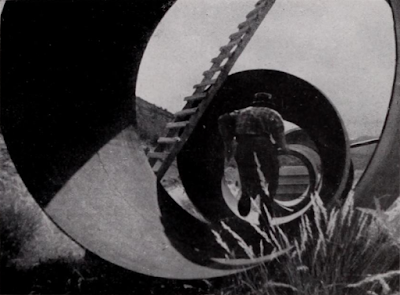

Above: a two-page illustration from Pierre Kast's article "Exercice d'un tragique quotidien: Notes sur l'oeuvre de Jean Grémillon". From La Revue du Cinéma, No. 16. August 1948. The right caption reads: "The combination of sound, noise, and image is, in Gremillon's work, capital to the very articulation of the story..."

Above: a two-page illustration from Pierre Kast's article "Exercice d'un tragique quotidien: Notes sur l'oeuvre de Jean Grémillon". From La Revue du Cinéma, No. 16. August 1948. The right caption reads: "The combination of sound, noise, and image is, in Gremillon's work, capital to the very articulation of the story..."Here, dreaming (like Jean-Daniel Pollet after him) of silent techniques rather than the raw reportage used in a film like the admirable La Liberation de Paris, Grémillon reveals, in a scene that parallels one in L'Espoir, the same structural understanding as the "fiction" filmmaker Malraux. "The simple, unadorned account of his experience by the carpenter de Guerinel who, for the only time in his life, became the observer and navigator of a bomber in order to locate a German artillery emplacement for allied air-men." (Pierre Kast.)

So on the one hand there is this insistence on a cinema of responsibility, a popular cinema combining the strengths of fiction and non-fiction, and the values of craftsmanship with the inspiration of an auteur. There is that description of "everyday tragedy" (Kast), firmly rooted in France and its trades, customs, speech and provinces: "To understand and to show the real social circumstances of the time, to reveal the inner contradictions of the regimes imposed or suffered: here is a starting point for those who tomorrow will bear witness to an epoch now approaching maturity." This is the Grémillon to be found in his most accomplished films, in his mastery of his material, whether an abstract dramatic device (Gardiens de Phare), a social tapestry (Lumière d'Eté, one of the best critical hommages to Renoir and La Règle du Jeu) or a tribute to the crafts of France (the last shorts: La Maison aux images, 1955, Haute Lisse, 1956, Andre Masson, 1958).

But another aspect, ignored in critical commentaries yet glaringly obvious in the films themselves (even though their air of euphoria may seem to contradict the point) lies in the affirmation of the impossibilities of harmony, the conflicts between love and vocation resolved without the mythology which seems consubstantial to them, the social contradictions that explode in sexual frustrations. It was Sadoul, in an article published during the Occupation, who linked de Sade and Aragon together in connection with Lumière d'Eté, the most explicit of Gremillon's films in this respect: "Eagerly awaited as a hero, master of women and destiny as well as of himself, the artist falls drunkenly off his motor-cycle and immediately establishes himself as the demoralized Hamlet in whose costume he ultimately dies. The aristocratic owner of the chateau is at first merely an insignificant, excessively well-bred young man. Gradually the veneer cracks and begins to peel away, revealing a monster ravaged by regrets, vices and evil passions. His costume at the masked ball completes the transformation into a degenerate libertine from another age of decadence. He is not so much des Grieux as some manic hero from de Sade—Dohnancé or Blangis—possessed by lust and murder and destined either for exile or the guillotine, as the Hamlet at his elbow predicts, mindful of Ribérac's example and careful to speak obliquely of rats and the kingdom of Denmark."

This lesson taught by Ribérac (or strictly speaking by Aragon)—the use of metaphor and allusion in art to encourage resistance—may be seen as applying to Grémillon not if he is taken as the Jacques Becker he is claimed to be (he is much closer to Renoir) but if one acknowledges the basic ambiguity of his work. For connoisseurs of the Hollywood cinema that was so foreign to Grémillon, it seems self-evident that the role played by the conditions and limitations of the commercial system could not be purely negative. So Grémillon tends to be noted more for an "enduring'" baroque quality than for the "realism" that is linked to historical circumstances. This stylistic reduction probably makes it difficult to see the merits of an approach to cinema (however hesitant) which attempts to affirm the realistic norm and, simultaneously, its exception.

Translated by Tom Milne

Postscript by Richard Roud: Grémillon is not only underrated outside France; he is almost totally unknown. True, in the days of Sequence, Lumière d'Eté had a certain reputation in Britain. But he made a number of other interesting films, too. In France he has not been entirely forgotten: Jean-Marie Straub claims him as one of the directors whose use of sound most influenced him. (Indeed Straub has gone on to say Le 6 Juin à l'Aube is the film that made him become a filmmaker—A.R.). Cocteau cryptically epitomized him as "A singular being in a plural world."

Originally published in Cinema: A Critical Dictionary, Vol. 1, edited by Richard Roud. London: Martin Secker and Warburg. 1980.

Reprinted by permission of Bernard Eisenschitz.

See Grémillon's Le 6 Juin à l'Aube (1944-45) along with Straub's Gens du lac (2018) and Peter Nestler's Väntan (1985) at the Echo Park Film Center on Sunday May 20, 2018 !

See Grémillon's Le 6 Juin à l'Aube (1944-45) along with Straub's Gens du lac (2018) and Peter Nestler's Väntan (1985) at the Echo Park Film Center on Sunday May 20, 2018 !

*

**

*

Also published today: Bernard Eisenschitz's letter to Godard (in French and English) after having seen Godard's latest feature, Le Livre d'image (2018).

1 comment:

Thank you for this! Do you have any idea which film the other clip comes from?

Post a Comment